At a recent work week in the lovely French town of Douarnenez we laid the groundwork for an upcoming feature in Kinto: Notifications!

tl;dr

For those that are in a hurry, here's the gist: We're going to be integrating a "notifications" system into Kinto with an eye towards simplicity, modernity, and flexibility. Our goal is to provide a solid framework that will allow other systems to take advantage of this new feature without having to jump through too many hoops. If that sounds interesting to you - read on.

Why?

The simple answer is that we have an itch to scratch at Mozilla. There is a platform called Balrog which is part of the update system used by Firefox and other Mozilla products. As part of an initiative to extend and improve the update process (the "Go Faster" initiative), we needed to store and transmit small, discrete blocks of information both between internal systems, as well as out to all of our users in the real world. Kinto has almost all the functionality we need except for one thing: notifications.

No problem. We can do that.

But wait, there's more!

Sure, Kinto is a Mozilla project - but it's meant for general use, which means that anything we design needs to be reasonably generic. With this in mind we committed to designing something that can be used in a variety of contexts; after all, we're an organisation built for and on the web, and as such, we're dedicated to using web-centric solutions.

Thinking then about what sort of parameters a reasonably generic solution might entail lead us to a few basic guidelines for designing the notifications mechanism:

- We should strive to be as agnostic as possible, meaning that locking into a particular service, back-end, or even programming language, should be avoided where possible.

- Since we're web-centric, we should capitalise on HTTP wherever possible as well.

- The notifications mechanism must be able to scale with a minimum of hardship; this applies to any eventual queues, workers, and so forth.

- Finally, it must be robust - we can't be losing messages now, can we?

What?

Before we go into the gritty details, let's take a moment to describe the overall picture of what we're trying to accomplish - on paper, at least, it's fairly straightforward:

- A message is a chunk of information which is being sent from one place to another - for example, an HTTP request. Messages can come from somewhere else, such as an external service, or can be generated internally.

- An action is some sort of processing which occurs as a result of the message. This could be something simple like incrementing a counter in memory. Alternatively, it could be much more complex - triggering a test and build process, for example. These can be native functions of Kinto, local executables, features from plugins, or just about anything else.

- A result, as the name implies, is the outcome of the action. A simple example would be the aforementioned in-memory counter, expressed as an integer, and wrapped into a nice JSON package. Alternatively, it could be the meta-data results from that theoretical build and test process (the possibilities are endless).

- Taken as a whole, events can therefore be thought of as a cycle: a message is received, an action takes place, some work is accomplished, and a new message is generated.

A notification is the combination of an incoming message and the action which is subseqently triggered. The result, while related directly to the action, is not itself part of the notification.

It's a fine distinction that bears further explanation. The originator of the incoming message isn't necessarily concerned with what Kinto does with the data - in general, it's sufficient to know that Kinto has received the message and that it will be treated appropriately. In this way we can maintain simple promises between each of the components in the greater system.

In any case, we'll explore some more terminology later - but for now let's move along.

How?

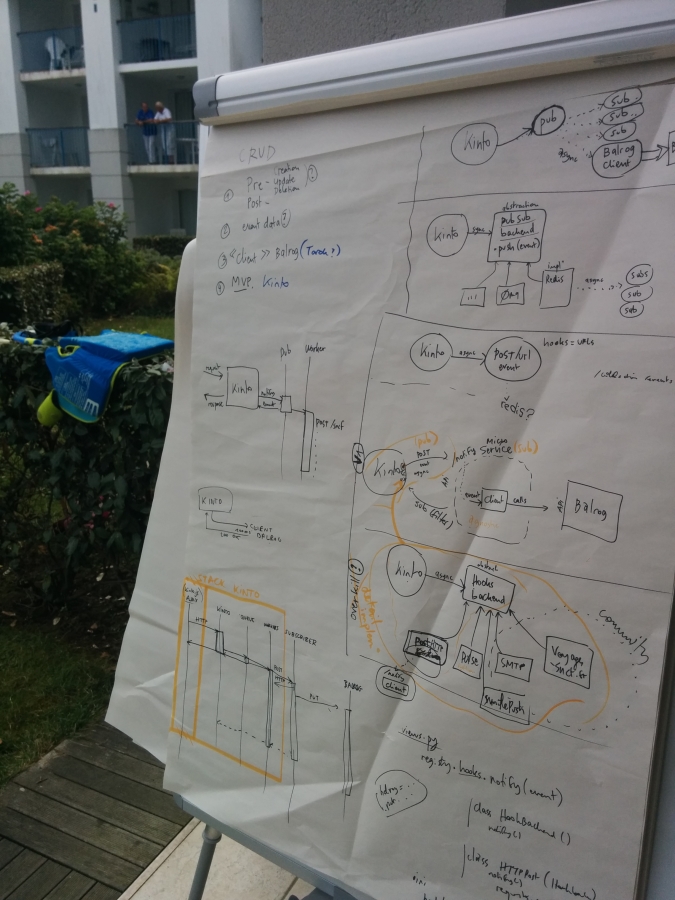

There are about as many ways to go about solving the problem as there are grains of sand on a beach (warning: previous statement may not be scientifically valid). The best way to determine the winning approach is simple: through single combat, Thunderdome-style. Unfortunately our manager put the kibosh on that plan for liability reasons, so instead we did the next best thing: we drew on a whiteboard.

In the interest of absolutely transparency, here are some of the models that we worked through and our general observations on each.

The Simple

One approach is to be as hands-off as possible. The premise here is straightforward enough: Kinto drops notifications into a queue (like Redis or RabbitMQ). That's basically it.

Pros:

- This model implies a highly limited scope insofar as Kinto is directly concerned; we would basically treat Kinto like a lightweight transport mechanism, and the queue as a fire-and-forget target.

- The amount of additional code would be relatively small - in essence, only just enough to speak to a queue service and nothing more.

- Depending on how active the community was, we would be able to support a reasonably large number of external queuing services.

Cons:

- Each queuing service would require a dedicated module to be coded and maintained, the responsibility for which would likely fall to the community as part of the larger ecosystem.

- It's ultimately up to the final consumer (receiver, destination, whatever) of the message to deal with the queue. In other words, if the queue is RabbitMQ, then the consumer needs to able to speak RabbitMQ too.

- Kinto has no control, understanding, or insight into what happens once the message is handed off to the queuing service.

The simplicity of this model, while attractive, has some fatal flaws. Chiefly, it runs contrary to our guideline of tech agnosticism as it would impose a particular external service dependency on the consumer. Furthermore, this model flirts with danger in terms of robustness as the fire-and-forget model isn't exactly optimised for reliability (not all queuing mechanisms are better than others, however).

The Integrated

We then considered what might happen if we were to swing the pendulum directly to the opposite of the spectrum from the previous solution. In this model, we would tightly couple the queuing service directly within Kinto and provide an API that the consumer could subscribe to.

Pros:

- Kinto could be shipped as a "turn-key" solution with a fully functioning stack baked right in; while there would be a queuing service involved (Celery, for example), it would be completely abstracted by Kinto.

- Since the queuing mechanism is integral, Kinto would have full visibility and control over processing and delivery.

- Apart from the queuing service there would be no additional services or software to deploy.

Cons:

- This would involve a fairly serious increase in the scope, complexity, and size of the Kinto code base.

- The tight coupling means that Kinto, in its entirety, would need to be re-deployed if changes were necessary in the queuing service.

- Similarly, scaling the queue would imply scaling Kinto itself

This model has certain interesting advantages; however, the relative volume of additional code that would need to be developed is reason enough to give us pause (scope creep is a real problem). Like the previous model, this also runs afoul of our tech agnosticism guideline since we would be locking Kinto to a given queuing service directly. Finally, we have (admittedly theoretical) concerns about how this model would scale - it feels like a waste to increase two resources when only one needs to grow, for example.

The Broker

The final approach is a bit of a mix of the previous two. In this model, we implement a formal "broker" that is part of the Kinto eco-system, but external to Kinto itself. The broker could be anything from a few lines of Python sitting on a pipe to a proper micro-service stack. This decouples the queuing mechanism from Kinto while preserving a strong promise of interoperability and control.

Pros:

- Provides a clean and easily understandable separation of responsibilities.

- Frees both Kinto and the consumer from any particular service dependency since the transport is pure HTTP between all the components.

- Permits the broker to scale independently from Kinto.

- Requires only a moderate amount of new code in Kinto itself.

- Effectively allows for a highly flexible solution where just about anything imaginable could be plugged in.

Cons:

- The broker must speak HTTP and respond properly to a specification of our choosing.

- Functionally requires deploying and maintaining two services (the difficulty of which varies according the complexity of the broker).

We like this model because it satisfies most of our guidelines (and violates none). To be fair, the requirement for "robustness" is a little hand-wavey in this case. We are effectively handing the responsibility to another component; however, since interoperability is a promise, we can maintain an acceptable degree of confidence in the process.

Another interesting aspect of this model is that by by decoupling the broker from Kinto, one can more easily introduce business logic that would be inappropriate within Kinto itself. A notable example of this is error handling - the manner in which we deal with, say, Balrog delivery issues isn't necessarily universal, and wouldn't make any sense outside of our particular use case.

A final point worth mentioning here is that the broker could, in principle, be the consumer itself, which fits into some of the potential use-cases at Mozilla quite nicely.

Roadmap

As you may have guessed, we've decided to go with the third option (The Broker). From here we have a plan to get from idea to reality, starting with a proof of concept, then through to a minimum viable product, and then iterating through improvements until we get to something that's useful to a wider audience.

Concretely speaking the proof of concept will require:

- Defining the types of events; functionally, this means specifying the behaviour and scope of

pre-andpost-patterns, as well as the structure of the payload. - Construct a framework for synchronous internal Python events using Pyramid events (something we have experience with already).

- Implement a "listener" in Kinto for those events in order to execute an action.

From there, we'll move on to the minimum viable product:

- Build a minimalist HTTP service that receives a notification via an HTTP

POST, performs an action, and communicates the result to Balrog directly.

Once the model is validated we'll begin the iterative improvement process. This will likely take the form of a "standard broker" which we create and maintain as part of the formal ecosystem. We also like the idea of subscribers registering themselves to the broker using an endpoint (such as webhooks), but that's a discussion for future time.

Feedback

As always, we're interested in feedback from the community - feel free to use the Disqus form below to join the conversation!

Revenir au début